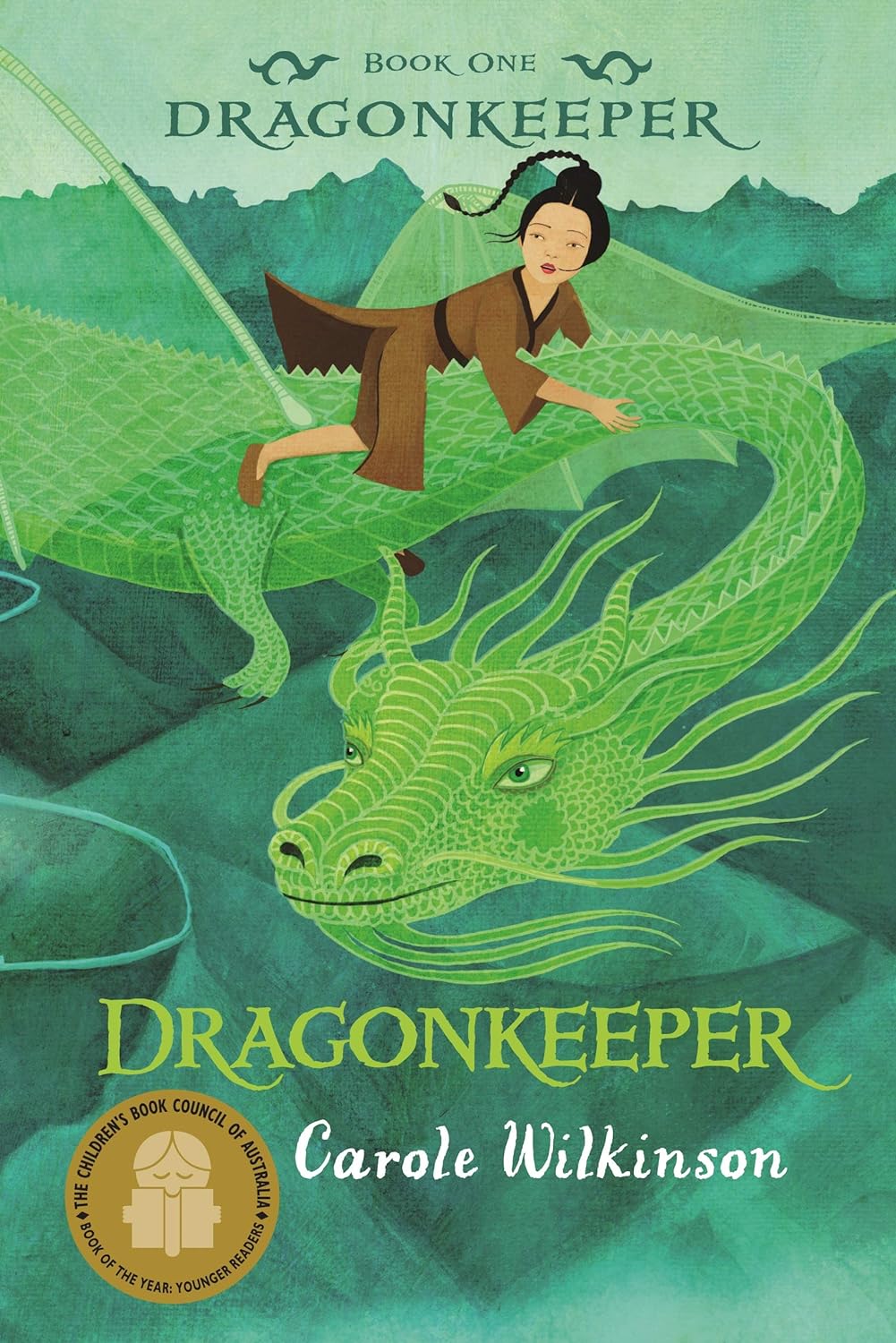

An author friend and I went bookstore hopping last month. One of the stores was dreamy. It wasn’t magical or aesthetic, it was everything you’d expect from a forgotten bookstore. The isles were narrow, the lighting was dim, and shelves were stacked with used books filling every inch. Among them, I found Dragonkeeper by Carole Wilkenson.

I skimmed the first chapter, the back, and had to buy it. It’s a scholastic book, after all. Eager to dig into this east-Asian, alternate-history, fantasy book, I cracked open the yellow, wrinkled pages and began the journey.

Dragonkeeper begins with an 11-year-old slave girl without a name. She endures the abuse of her drunken master and cares for the imprisoned imperial dragons in the forgotten icy palace. Right out the gate, one of the dragons dies and a horrible scene ensues with everyone hoisting the dragon out of the dungeon to be pickled while the last dragon howls his sorrows.

Shortly after, the emperor arrives for the first time in the girl’s life. He sells the last dragon to an evil hunter and, feeling some responsibility for the first dragon’s death, the girl helps the dragon, Danzi, escape.

It is at this point that we finally learn the girl’s name: Ping. I try very hard not to judge character names because I know how hard they can be, but after waiting four chapters, I expected a better name than Mulan’s clumsy alias.

Being hunted by the empire, Ping is forced to accompany Danzi on his fantastical journey to the ocean. Ping, her trusty sidekick (Hua), and Danzi face various hurdles and suspicions throughout the book barring the way to their destination, and the dragon hunter comes back throughout the book as the primary antagonist, though I wish he was seen more in the final act.

Throughout the book, Danzi speaks in broken sentences except when he is giving wise counsel which feels inconsistent. Wilkenson writes at the end of the book that these wise sayings are based on ancient Daoist philosophy, also known as Taoism. This way of speaking felt natural for the dragon and the book would have benefited from him consistently sounding sophisticated.

Though the writing level is simple enough for the 7-10-year-old target audience, you will have to look up the glossary for several words. However, the value of a moral gray is too complicated for young readers (more on that in negative messages).

Overall, I was very disappointed with Dragonkeeper. As someone writing in east-Asian fantasy, I was ecstatic for this scholastic book, but it fell flat. Wilkenson kept secrets for no reason, she told so many things she could have shown, and the values taught were mediocre at best.

Although I have set the recommended reading age at 11+, I wouldn’t recommend this read.